Film Score: John Leipold Cinematography: David Abel

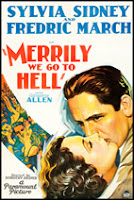

Starring: Sylvia Sidney, Fredric March, Adrianne Allen and Cary Grant

Another early pairing of Fredric March with the positively luminous Sylvia Sidney for Paramount, Merrily We Go to Hell is a pre-code picture focusing on alcoholism and adultery. The film is based on the short story “I, Jerry, Take Thee, Joan,” by author Cleo Lucas. If there’s any real merit to the story itself, it is due to the female point of view by Lucas, and the tremendous talents of director Dorothy Arzner, a similar take on the idea as 1930’s The Divorcée at MGM from a novel by Ursula Parrott but with a more traditional ending. The throughline for both is a kind of domestic tragedy that is utterly absent from today’s screen. While the pre-code era is known for sex and violence, one of the aspects of those films that gets little attention is the emotional devastation emerges out of domestic relationships that are doomed from the start. The love that overcomes those warning signs in the early days is then gradually eroded away until one of the partners—primarily the woman—is faced with a choice that is as gut-wrenching as it is real. Modern trauma-dramas not doubt wish they could emulate the kind of intensity of emotion that these stories produced in abundance, but there’s nothing like the original for emotional power that has never really been captured in the same way since.

Chicago newspaper man and unproduced playwright Fredric March is a lush, drinking to forget having his heart broken by actress Adrianne Allen. At a party he meets manufacturing heiress Sylvia Sidney, and his frankness and undisguised genuine attraction to her causes her to fall in love. March is honest about his past, but she agrees to marry him anyway, though he likes to spend most of his free time at swanky speakeasys. Many of his co-workers, especially Charles Coleman, believe he’s not over Allen and only marrying Sidney for the money. Sidney’s father, George Irving, agrees and invites March over before the wedding to offer him fifty thousand dollars to walk away. March refuses, of course, and this endears Sidney to him even more. Nevertheless, Irving provides the couple with a living so that March can write his plays, but they are uniformly rejected and with little hope that they will ever be produced, and his failed career gnaws at him. Then the unexpected happens, when a producer expresses interest in his play and invites him to New York. But of course, March is still a drunk, and much more interesting to Allen than he was before, especially when she’s tabbed to star in the play. And it’s then the gears of pre-code tragedy gradually begin to grind up Sidney and take the audience along on the brutal journey with her.

March is solid, and while he’s a bit artificial onscreen it was not something he ever developed out of even later in his career. Which is not to say he’s necessarily bad, as he’s obviously talented, is just that he always seems to be playing to the back of the house. Sylvia Sidney, on the other hand, is a tremendous talent, capable of projecting a wealth of emotion through simple gestures of her face, and without raising her voice—though she’s undercut in that respect by the needs of the early sound film mechanics. The real stars of the picture, however, are director Dorothy Arzner and cinematographer David Abel. Arzner uses some truly impressive moving camera work from Abel, and together they create a style that gives a convincing precursor to what the hand-held camera was able to do decades later. Many of the shots are beautifully composed, and while they don’t necessarily draw attention to themselves, are incredibly advanced for the period. It’s a testament to female directors like Arzner, that their male counterparts for the most part were not nearly as creative and artistic behind the camera. Other actors of note are Richard Gallagher and Esther Howard as March’s best friends, and a brief appearance by Paramount contract player Cary Grant. Though the story is typical fare for domestic pre-code tragedy, director Dorothy Arzner and the talents of March and Sidney combine to make Merrily We Go to Hell a rewarding viewing experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment